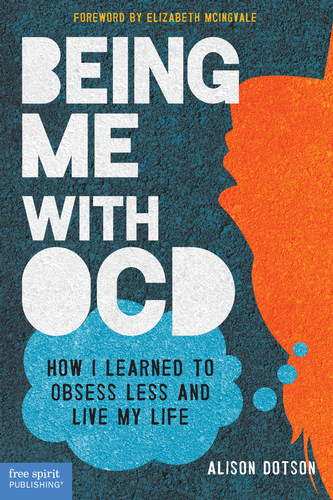

Welcome to another awesome AiT Exclusive Interview, this time with Alison Dotson, author of Being Me with OCD: How I Learned to Obsess Less and Live My Life! Join us as we talk through her book, her personal journey with OCD, and advice share has for young adults struggling with OCD.

AiT: You had, of course, experienced OCD yourself. Sharing about OCD isn’t exactly easy, what was your inspiration for taking the leap to write the book, Being Me with OCD: How I Learned to Obsess Less and Live My Life?

AD: I suffered for years and years, wondering what was wrong with me, wondering why I was having incessant, upsetting sexual and religious thoughts that were counter to my morals and beliefs. I didn’t know anyone with OCD, and I thought it was all about a germ phobia and handwashing. Well, I don’t have a germ phobia and I wash my hands after I use the bathroom or when my fingers are covered in Doritos dust. In my mid-twenties I hit a breaking point: Either I got help or I ended my life. I couldn’t take it anymore–the guilt, the pain, the doubts. Before I did anything drastic, however, I asked a good friend what she knew about anti-depressants. We got to talking, and I mentioned that I obsess about a lot of things. She said, “A lot of people with OCD take Paxil. Not that you have OCD, but you said you obsess, so it might help.” (Paxil isn’t the only medication that helps individuals with OCD, though!) OCD had never occurred to me, but I was so desperate for answers I started looking into it. It turns out sexual and religious intrusive thoughts are indeed a symptom of OCD! And you don’t have to be a compulsive handwasher to have it. I found a scholarly article about how therapists can help people with sexual obsessions, and my mind was blown. It wasn’t even written for me, but I felt incredibly relieved. I wasn’t alone. Others had these obsessions, too, and there was help. That’s why I wrote Being Me with OCD. I wanted people just like me to have a resource that let them know they aren’t alone, they aren’t unlovable, and their obsessions and compulsions aren’t untreatable. I wanted them to have something other than a scholarly article, teens especially. I pushed through my doubts and fears about sharing my very personal story, and I’m so glad I did.

AiT: In your book, you showcase stories from other young people’s’ lives and the OCD experiences they’ve endured. Were you surprised to learn the content of other people’s’ OCD? Was it more or less diverse than you expected?

AiT: In your book, you showcase stories from other young people’s’ lives and the OCD experiences they’ve endured. Were you surprised to learn the content of other people’s’ OCD? Was it more or less diverse than you expected?

AD: I was surprised at how hard it was to find someone with contamination fears or a handwashing compulsion! After thinking for so long that those were the only symptoms of OCD, I ended up with a variety of experiences. Since writing the book I’ve learned of so many obsessions and compulsions I wasn’t aware of. OCD is all about fear and doubt, and that can come in any number of forms.

AiT: I loved the chapter on Everyone and Their Brother Think They Have OCD. I personally struggle with getting frustrated with people making OCD, a debilitating disease, something to use as a joke or an adjective for super tidy or something. Do you have some suggestions for how young people can address these comments effectively?

AD: Decide on a case-by-case basis whether you want to enlighten someone who’s made these comments. Sometimes a co-worker will say something like “I’m so OCD about my files!” and I make a split-second decision on how I’ll handle it. If we’ve talked before and generally get along (and I won’t embarrass them in front of anyone), I might say, “Oh, you have OCD? I do, too!” That way, if they really do have OCD but just expressed it in a way that usually bothers me, they now know they have someone to talk to about it. If they don’t have OCD, they might realize that having the disorder and “being OCD” are not the same thing. I make it lighthearted or joke a little so I can still get the point across without shaming someone. It bothers me a lot, but I have to remember that most people are simply misinformed and don’t realize they’re being hurtful, so I try to be kind. You may not feel comfortable talking about your own OCD, but you can still use these uncomfortable situations as teaching moments. “You know, I always thought that OCD meant being really organized, but then I saw this great video, and I learned a lot!” This can be particularly effective on social media because you can link to videos, websites, and articles. If you’re in a vulnerable place in your recovery, be aware that people don’t always take criticism well, even when it’s well-intentioned and delivered with tact. Some people think “PC culture” has gone too far and refuse to bend. Consider how ready you are for a disagreement before you correct someone. I’ve had people say really rude things to me on Twitter, but in person most of these interactions have been pleasant. (Also, prepare yourself for the very real and frustrating possibility that you will give an Oscar-worthy presentation on OCD, only to have someone approach you and say, “I’m really OCD about color coordinating my closet!”)

AiT: Also in the book, you talk about your relationship with your now-husband Peter and disclosing your OCD to him. How did you know it was the right time to tell him?

AD: The right time for me was immediately after I was diagnosed. I hadn’t told him about any of my obsessions because I was afraid he’d hate me and think I was a ticking time bomb who was going to act on them, and even though he noticed I wasn’t myself I downplayed my depression–even when I considered ending my life. But I did tell him I wanted to go on antidepressants, and he knew I had an appointment with a psychiatrist, who ended up diagnosing me with OCD. I called Peter and said, “Your girlfriend has OCD.” He said, “Sounds about right.” Pretty sure he asked what I wanted for dinner next. I felt a huge sense of relief, but it was a long time before I felt ready to divulge personal details. Instead, I asked him to read The Imp of the Mind by Lee Baer and said, “This is me. I relate to the people described in this book.” It was really important to me that he understand what I was going through, but I needed a little cushion between my own obsessions and him.

AiT: How do you wish Being Me with OCD: How I Learned to Obsess Less and Live My Life could help impact young people dealing with OCD?

AD: First and foremost, I hope readers realize they’re not alone! OCD can be such an isolating disorder, and I can’t tell you how many people think they’re the only person on the face of the earth, in the history of the world, to have experienced this. No matter your type of OCD, no matter the theme of your obsessions, there is help available. There is hope. Having OCD may be a part of you, and it may take up more of your life than you want, but it doesn’t define you. I hope reading Being Me with OCD will encourage people to seek help and open up about their pain.

About Being Me with OCD: How I Learned to Obsess Less and Live My Life: Part memoir, part self-help for teens, Being Me with OCD tells the story of how obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) dragged the author to rock bottom—and how she found hope, got help, and eventually climbed back to a fuller, happier life.

- Where to purchase Being Me with OCD: How I Learned to Obsess Less and Live My Life:

- From my website

- Amazon

By: Solome Tibebu, AiT Contributor